A nation of immigrants

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

–The New Colossus, Emma Lazarus, 1883

These words are inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty, perhaps the most famous and most recognized symbol of democracy and enlightenment in the world. Commemorating the centennial anniversary of the Declaration of Independence and honoring the friendship of the peoples of the United States and France, the statue was presented to the American minister to France in Paris on July 4, 1884. The completed statue was later disassembled and shipped to New York City and unveiled in New York Harbor on October 28, 1886. Because of its location near Ellis Island, where millions of immigrants were received until 1943, the Statue of Liberty has also come to be a symbol of hope, freedom, opportunity, and justice.

This country’s history and view of itself as a nation of immigrants has been a politically-charged ideal almost since the country’s beginnings. Indisputably, the US has more immigrants than any other country in the world, and the share of immigrants among the US population is growing dramatically. The US foreign-born population reached a record 46.6 million this year, accounting for about one-fifth of the world’s immigrants. This number has more than quadrupled since 1965 and now accounts for 14.2% of the US population. This is nearly triple the share (4.8%) in 1970 but still below the record 14.8% share in 1890, when 9.2 million immigrants lived in the US. Virtually every country in the world is represented among US immigrants.

For the first century of its existence, the US had completely open borders. Not until the Nationality Act of 1790 did the US take steps to define eligibility for citizenship and establish standards and procedures by which immigrants would become US citizens. While immigration was largely unrestricted, the right of citizenship was limited to “free white persons” until ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868 following the Civil War, which established birthright citizenship to all persons born in the US. (The Supreme Court, however, subsequently ruled in Elk v. Wilkins (1884) that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to Native Americans.)

Open borders for people of color came to an end in 1875, with the passage of the Page Act, effectively prohibiting the entry of Chinese women, followed by 1882’s Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned men as well. While the Immigration Act of 1882 and other laws did impose certain limited restrictions on white immigrants, including anyone “likely to become a public charge,” for able-bodied white men, open borders remained very much real into the 1920's.

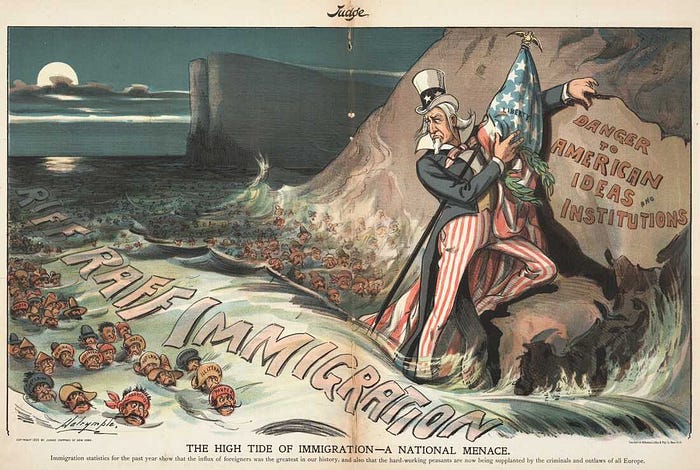

Sadly, despite an unmatched position as a “golden door” for the world’s immigrants and refugees, racist fear-mongering has set the tone for much of the immigration debate in this country and enabled an ugly history of restrictive, abusive, and dehumanizing treatment of many immigrants by the US ever since.

Ken Burns’ documentary The US and the Holocaust explores xenophobia in the US in the late 19th and early 20th centuries leading up to the rise of Adolph Hitler. Much of the history Burns presents is familiar, but much of it is not. While acknowledging the important and unique role of the US in the ultimate defeat of Nazism and fascism, Burns raises uncomfortable questions challenging the US mythology as a nation of immigrants, particularly relating to our policies toward Jewish refugees desperate to escape Hitler’s Reich in the 1930's and 40's.

In 1933, there were nine million Jews in Europe; by 1945, two-thirds had been murdered. Did this have to be the case? Burns challenges us to ponder what would we have done? What could we have done? And what should we have done?

To be fair, many Americans did protest Hitler’s aggression. Americans staged marches and rallies and instituted boycotts. Many Americans launched individual campaigns at great effort and personal risk. And the US ultimately accepted 225,000 refugees, more than any other country. But throughout this period between the wars, those who supported the Jews of Europe and urged intervention on their behalf risked becoming targets of hate and lies themselves. Racism was on the rise and being normalized. A resurgent Ku Klux Klan had reached membership of four million.

Not unlike today, ignorance and hate were not limited to the poor and uneducated but were often fueled by the rich and powerful in American society. Henry Ford was one of the most revered and influential men in America. He revolutionized manufacturing and created a foundation for America’s middle class, but he also vilified immigrants and Jews. After purchasing his local newspaper, The Dearborn Independent, Ford published a series of articles promoting a vast Jewish conspiracy, which he bound into four volumes entitled “The International Jew.” Ford’s writings grew circulation at the paper to the second highest in the US and earned him the distinction of being the only American complimented by name in Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Ford was also a high-profile early member of the America First Committee, which claimed 800,000 members in 450 chapters, making it one of the largest anti-war and anti-immigrant organizations in US history. Ford’s friend and American icon, Charles Lindbergh, would become its most prominent speaker, promoting his isolationist, antisemitic views. “Imagine the United States taking these Jews in in addition to those we already have,” he wrote. “There are too many in places like New York already. A few Jews add strength and character to a country, but too many create chaos. And we are getting too many. This present immigration will have its reaction.” New York has long been a potent symbol for anti-immigrant rhetoric. In 1920, the 1.5 million Jews in New York City represented more than one-quarter of its population.

A few Jews add strength and character to a country, but too many create chaos. — Charles Lindbergh

Following the success of the Emergency Quota Law of 1921 at dramatically reducing the flow of immigration into the US, particularly from Eastern Europe, the Immigration Act of 1924 (the Johnson-Reed Act) permanently extended the discriminatory system of “national origins” quotas. The quota system would become even more restrictive under Johnson-Reed and remain the primary means of determining immigrants’ admissibility to the United States until 1965.

Newly-elected Brooklyn Congressman Emanuel Cellar came to office determined to fight this bill, but he soon realized the fight would be in vain. “The United States was drawing her skirts about her in fear, lest she be contaminated by the alien. The temper of the Congress, I discovered, is the temper of the people.” It was he who was out of sync.

The quota system was largely based upon the bogus “science” of eugenics, the specious and immoral theory that was gaining popularity and being used to rationalize the racist Replacement Theory and as a means to Race Betterment. (Thirty-three of the 48 states allowed forced sterilization and 60,000 Americans had been forced to undergo the procedure without their consent.) The new quotas were set at two percent of each group’s population according to the 1890 census. This figure came from a Report of the Eugenics Committee of the United States Committee on Selective Immigration. The 1890 census was used rather than on a more recent one in order to achieve “a preponderance of immigration of the stock which originally settled this country.” North and West Europeans, read the report, were of “higher intelligence” and hence provided “the best material for American citizenship.”

Hitler’s regime found support for its race-based initiatives in American history and law. The US treatment of Native Americans laid an early justification for Hitler’s resettlement, expulsion, and extermination of Germany’s — and later, Europe’s — Jews. But 1920’s and 1930’s America was equally ripe with codified racism. Under President Hoover’s racially-coded slogan “American jobs for real Americans,” the US deported and repatriated as many as 1.8 million Mexican-Americans, 60% of whom were US citizens. Occurring without any due process, the Mexican Repatriation Program meets the modern legal standard for ethnic cleansing.

And in Hitler’s American Model, Yale law professor James Q. Whitman makes a case “that the Nuremberg Laws themselves reflect direct American influence.” Beyond Jim Crow, discriminatory US laws governing Native Americans, citizenship for non-whites, immigration regulations, and prohibitions against miscegenation in 30 states provide direct corollaries for codified race-based discrimination.

Because Hitler rose to power propagating the Big Lie that the German army had not, in fact, been defeated on the battlefield in 1918, it’s impossible to know for certain how much he actually believed his own theories about race. His Big Lie insisted that a cabal of “November criminals” — Jews, Marxists, democrats, and internationalists — had betrayed the country, subverted the war effort, driven out the kaiser, signed the shameful Treaty of Versailles, and imposed an un-German democracy.

In Mein Kampf, Hitler explained that “the masses … more easily fall victim to a big lie than to a little one,” and that even a propaganda claim “so impudent that people thought it insane” could ultimately prevail. Essential to a conspiracy theory’s effectiveness were a simple appeal to emotion and endless repetition without concession. Commitment to the Big Lie, he realized, had to be complete and unyielding.

His hatred for the Jews was possibly as much political as it was racist. According to Northwestern historian Peter Hayes, not only did Hitler view the Jews as dangerous for their genetics but for the ideas they represented. Jews were responsible for the ideas of conscience, fair play, the golden rule, and international cooperation, all of which were reprehensible to Hitler and antithetical to Nazism. Yale historian Timothy Snyder agrees. Hitler saw the Jews as responsible for every global idea, every universal idea, anything that allows us to see each other as people rather than as members of a race.

Amidst this anti-immigrant and isolationist sentiment, Franklin D. Roosevelt was very cautious with action by the federal government. By the time of his re-election in 1936, his policies had started to turn the economic tide, but he was not supported in his desire to be a global leader. Already subject to antisemitic conspiracy theories claiming he was actually a Jew (supposedly born “Rosenfeld”), FDR was acutely aware that he was an internationalist leading a nationalist and nativist populous.

Despite the reporting and the evidence of Jewish persecution that had become difficult to ignore, public opinion was firmly opposed to US intervention. By 1938, two-thirds of Americans still believed that Jews were at least partially to blame for their plight. Large majorities of Americans, including one-quarter of Jews, were opposed to providing sanctuary for refugees or increasing immigration quotas. Hitler’s quick victories through Europe fed suspicion that spies were abetting the Nazis, implicating refugees as potential threats to US security. North Carolina Sen. Robert Rice Reynolds (D) spoke for many when he announced “I would today build a wall about the United States so high and so secure that not a single alien or foreign refugee from any country upon the face of this earth could possibly scale or ascend it.”

It wasn’t until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor forced the US to enter the war that FDR had an opportunity to do more for the Jews than the incremental strategies like pressuring Latin American allies to accept more refugees. But instead of attempting to rescue Jewish refugees directly, FDR focused US efforts on winning the war and thereby liberating Europe’s Jews. To the frustration of American Jewish leaders like Rabbi Stephen Wise, despite FDR’s creation of the War Refugee Board, this strategy largely prevailed through the end of the war.

Not until release of the Auschwitz Reports were Americans really prepared to confront the absolute inhumanity that had been inflicted upon the Jews. After the release of these eyewitness accounts, 76% of Americans finally believed the crimes against the Jews were real, but still only a fifth could accept that more than one million had died.

It’s too easy to judge past generations of Americans for their actions and their inactions. What would we have done, what could we have done, and what should we have done are interesting but intellectual and hypothetical questions. More important, What are we doing now? Who are we, really? And who do we want to be? The US and the Holocaust forces us to reconcile our own hypocrisy in the face of human crisis and injustice today.

The busing of migrants by Governors DeSantis and Abbot to Democratic cities may anger us in its audacity. And it may even recall the Reverse Freedom Rides of 1962, when Southern segregationists sent Black Americans to mostly Northern cities by bus with promises of high paying jobs and free housing, but so what? El Paso mayor Oscar Leeser, a Democrat, had been doing the same until this week. The issue is the humanitarian crisis not the political circus.

When we read the racist manifesto of Dylann Roof or hear the chants of “Jews will not replace us” from white supremacists in Charlottesville or witness the assault on the Capitol by domestic terrorists in “Camp Auschwitz” tee shirts or see antisemitic banners hung from a highway overpass, how must we respond? And if we fail to respond, what does it say about who we really are and what we really value?

Burns ends with the story of Joseph A. Wyant, a GI who was sent to photograph Dachau in 1945. Wyant wrote to his father “this particular crime has been uncovered, Pop, but a worse crime seems to be the spreading of the thought that leads to this type of thing. It has happened in mass proportions here in Germany but who knows how far the ideas have spread or where else it may break out? I tell you, Pop, even more important than punishing the criminals here is stamping out of their philosophy. This is not a war between nations but humanity’s struggle for the right to exist.”

Not a war between nations but humanity’s struggle for the right to exist. — Joseph A. Wyant

Reflecting on the consequences of American inaction in a 1946 speech, Eleanor Roosevelt said, “I have the feeling that we let our consciences realize too late the need of standing up against something that we knew was wrong. We have therefore had to avenge it, but we did nothing to prevent it. I hope that in the future, we are going to remember that there can be no compromise at any point with the things that we know are wrong.”

This piece began as a response to the busing of immigrants from Texas and Florida, but since I started researching and writing, acts of racism and anti-semitism have again ignited public debate. These issues are unfortunately never retired and hatred is never vanquished. If the US is to continue to be a beacon of hope, freedom, opportunity, and justice — for those who are here as well as for those who are yet to arrive — we must honor our noblest values and continue this fight.